Last month’s Google Analytics report said a top-three trending page on the teracomtraining.com site was the tutorial on voice digitization.

The material in that tutorial, graphics and text, was created in 1999 for a course workbook. But the fundamentals rarely change, and it is just as relevant and accurate today as it was then. Who are we to argue? Here it is again:

– – –

We look in detail at the voice digitization process to derive the data rate – number of bits per second – required to communicate a digitized voice signal, and understand the steps involved. Once the voice – half of a phone call – is digitized, it can be segmented and carried in IP packets along with everything else in the modern broadband converged IP telecommunications network.

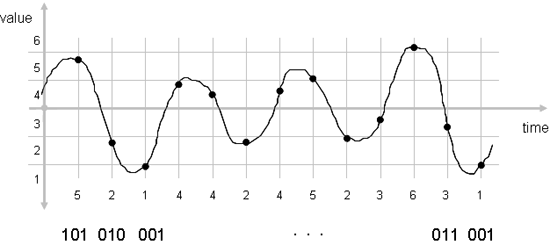

There are three steps in voice digitization: quantization, sampling and coding.

Quantization: Change from continuous in value to discrete in value

Sampling: Change from continuous in time to discrete in time

Coding: Code value of sample into standard-format 1s and 0s

Voice Digitization: Quantization, Sampling and Coding

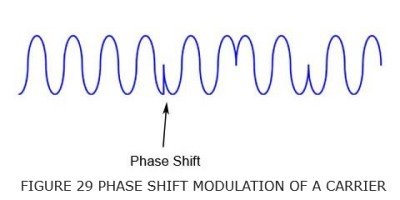

A continuous signal is one that exists at all values. Pick any two values, and there can always be a value between them… like the voltage on copper wires representing your voice when making a phone call.

A discrete signal is one that is defined only at specific values, and is not defined between… like the number of people in a room.

Quantization is the process of changing from a signal that is continuous in value to a signal that is discrete in value. This is accomplished by dividing the possible range of values into a number of bins or levels or steps, and assigning a number to each of these levels.

Later, when asked what the value of the signal is, we say that the signal is “in level #4” rather than quoting its voltage accurate to some number of decimal places.

Another example of quantization is sugar cubes. Instead of putting some random fractional value of a teaspoon of sugar in your coffee, your choices are “one lump or two”. The sugar has been quantized into uniform increments.

Many hardware chips implement 16-bit quantization, meaning 65,536 levels. These are consolidated into a smaller number of levels by software during the coding step below.

Sampling is the process of changing the signal from being continuous in time to one that is discrete in time: on a regular basis, we measure the value of the signal and record it. The value of the signal is recorded as the quantization bin number it was in.

How often do we need to sample the signal? A mathematician by the name of Nyquist proved that the signal has to be sampled more than twice as often as the frequency bandwidth of the signal to be able to reproduce it. This is called the Nyquist Rule.

The final step is coding. The value of the signal taken at each sample (the level number) must be coded into 1s and 0s so that it can be efficiently transmitted or stored in a computer.

We are interested in using standard coding methods like G.711 for landlines or the AMR codec used for cellular, so that any device or software app can decode the value at the far end. Skype uses a proprietary coding method, meaning that only the Skype app can be used to decode the values at the far end; whatsapp, for example, is not compatible.

The codes representing the value of the samples are then transmitted to the far end.

At the far end, the reverse process is performed: re-creating the analog waveform from the received codes by de-coding the level number, generating a voltage with a value equal to that of the center of the level, and smoothly changing the voltage in this manner as each new code comes down the line.

The objective of doing all of this is to move the analog voice signal from the near end microphone to the far end speaker, without adding in any noise.

Bonus: the digitized voice can be carried in IP packets interspersed with video, data and Internet traffic, on the modern broadband converged IP network.

There is in fact a small amount of noise added in, up front, as part of the analog-to-digital conversion. This is the quantization error, the difference in value between the center of the level, and where the signal actually was.

How do we make the quantization error smaller on average? Make the levels finer. How many levels does the telephone company use? Enough so that a human can’t hear the quantization error noise on the line. Read the exciting conclusion in